The Coming Crisis in Education

Schools and school leaders spend a lot of time thinking about many crises in education, but many of them focus on student trends: test scores, changing demographics, declining literacy rates and the like. But there’s another crisis that few people on campuses around the country focus on: changes in the teacher workforce. Ignoring this crisis is to the peril of students in all schools. As these changes continue to grow—and they will continue to grow—the negative impact on classrooms will become more apparent than it already is today.

In an October 2019 presentation to the Consortium of State Organizations for Texas Teacher Education (CSOTTE), the Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath shared some troubling statistics about workforce trends among Texas’ teachers. It’s always dangerous to extrapolate national trends from Statewide data, but similar trends have been cited by researchers at universities around the country and even the US Department of Education.

The most troubling statistics?

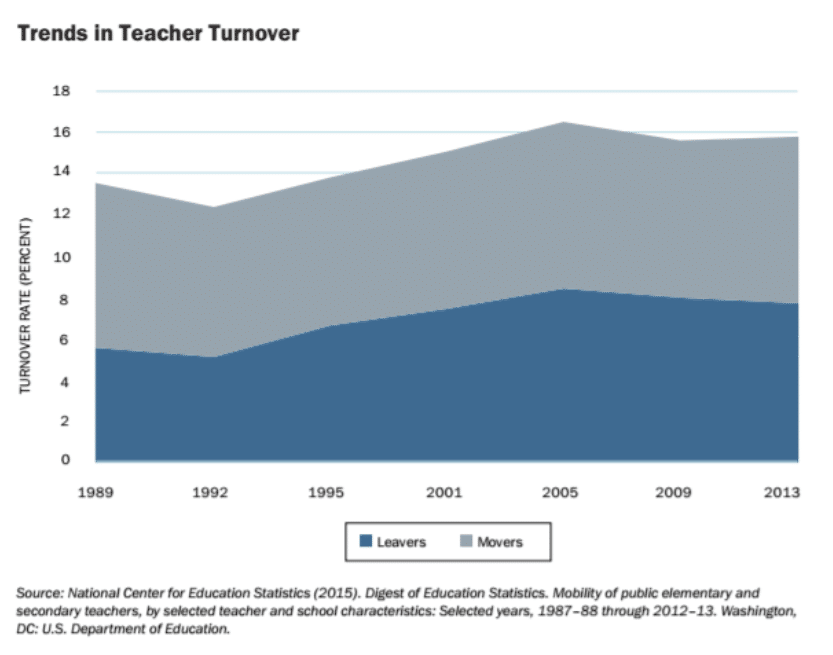

- 1 million teachers quit every year

- A growing number of those teachers aren’t quitting to go work at another school; they’re quitting teaching altogether.

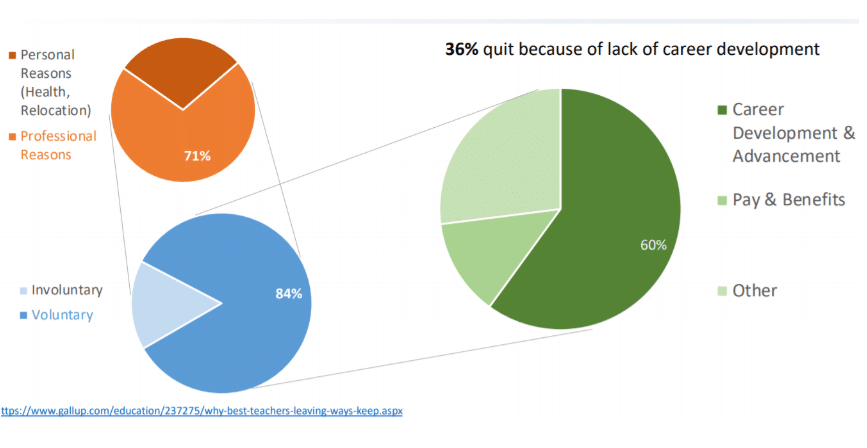

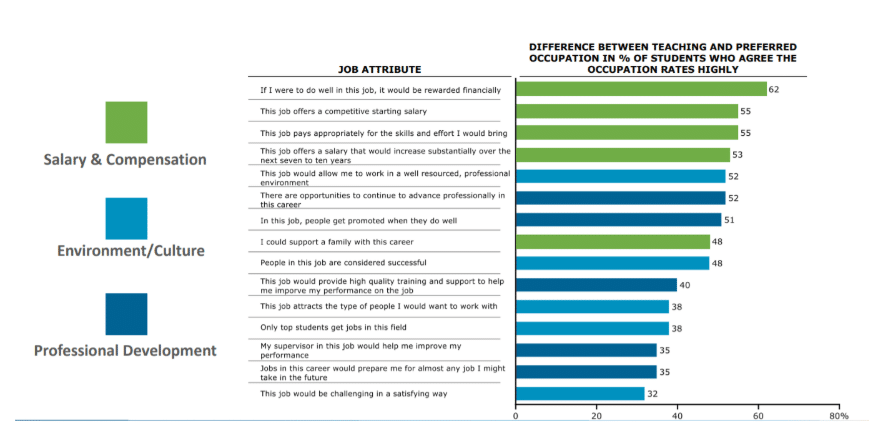

- 36% who quit, do so because they feel no career development opportunities exist for themselves.

Of course, with a total workforce nearing 4 million, it’s natural to see a large number of people quitting any job. However, the fact that so many, almost 300,000 teachers, are leaving the profession primarily because they see no opportunity for professional growth is troubling.

These trends are worrisome enough, but become even more worrisome when coupled with some additional statistics about the next generation of teachers.

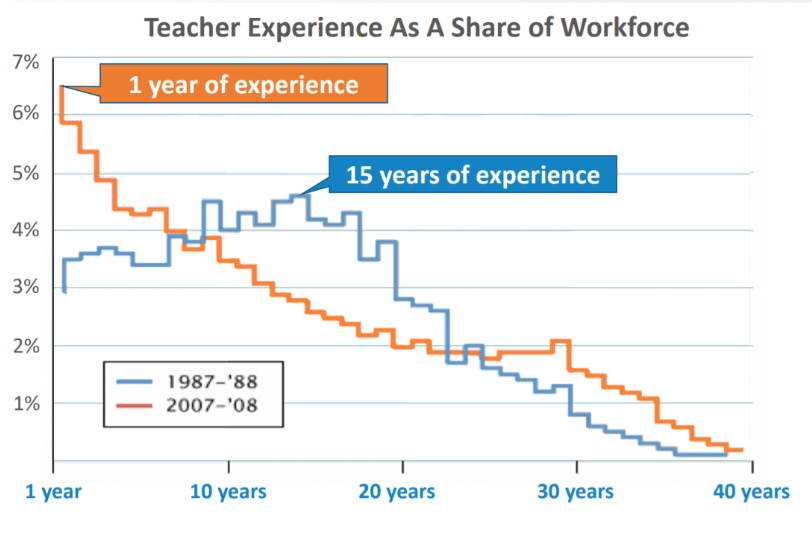

The average teacher has fewer years of experience in the profession than they have in decades.

Teaching as a profession is not popular to young Americans considering their future careers.

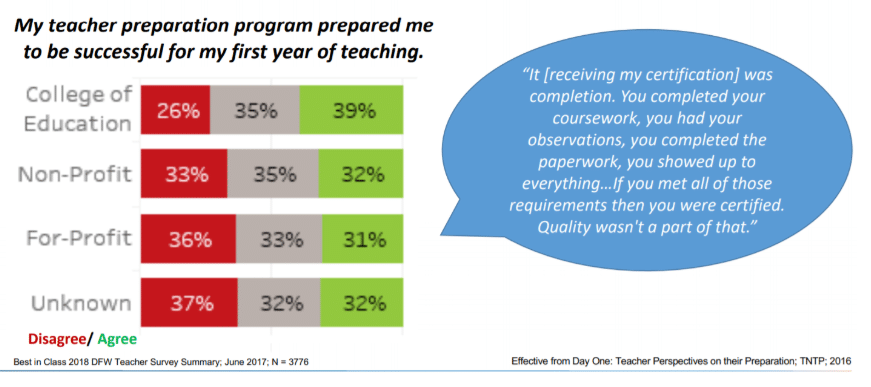

And 2/3rds of those who do pursue careers in teaching feel they are unprepared to do their job.

This is a perfect storm. The confluence of a growing population of disaffected teachers and a shrinking population of young people who are excited about and prepared for a life of teaching has two major consequences for schools:

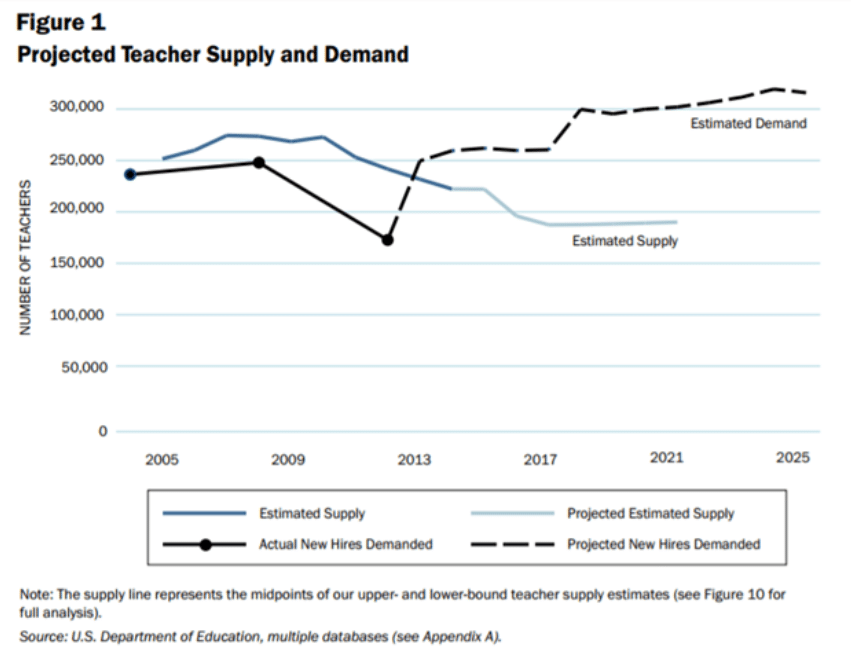

- The teacher shortage is going to grow dramatically. In fact, the Department of Education has estimated that the shortage will be in the hundreds of thousands by 2025. That’s hundreds of thousands of classrooms with no certified teacher in them. That’s millions of students crammed into already overcrowded classrooms. That’s hundreds of thousands of already overworked and disaffected teachers picking up the slack.

- The professional growth opportunities schools provide will become even more important. As more and more people choose an alternative path to teaching, many set foot in a classroom on day one with little formal training and no practical experience at all. This means that the fundamentals of teaching, a job previously relegated to universities and other teacher preparation programs, will now fall to schools.

So here’s the crisis: many teachers feel they are either unprepared or have little opportunity to develop new skills. Those who do feel they have learned new skills see no chance to be rewarded for those new skills. And they leave. Or, sometimes worse, they stay…unskilled and disaffected. The consequence is dire: we risk children being taught by people who don’t know how to do their jobs, are disgruntled about their jobs, or both.

And at the center of all of this is one part of education that gets, for the most part, a cursory glance and rhetorical support from most school leaders: teacher professional development.

And what do most schools do about it? They wring their hands and develop more of the same kinds of PD that they had before! Schools develop a larger quantity of one-time workshops that are measured only by attendance, they try to make PD workshops “fun” for teachers, they pay more consultants to come in and do large one-size-fits-few events, they change the name of department or grade level meetings to “Professional Learning Communities” with no substantive changes to the content. What don’t they do to develop teachers? Look to their most important asset: their teachers.

Much the same way that students should be at the center of all lesson planning, teachers should stand at the center of all professional development efforts in a school or school district. Not hypothetically, but actually. Teacher skill data should inform all planning. And the actual teacher expertise of any organization should be the locus for all support. All teachers do something well, and no teacher does everything well. By building opportunities for teachers to connect with one another in small groups based on their needs and strengths, share with one another, and be rewarded for that sharing, schools will give teachers a chance to grow and feel a sense of validation for that growth (rather than the silly certificate of attendance that arrives at the end of most workshops). There’s plenty of money for it. Schools spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on consultants and PD presenters each year. A simple reallocation of funds can distribute those dollars to teachers who contribute to their own and others’ learning. Some innovative schools are doing this already. And many teachers are as well. Entire ecosystems like Teachers Pay Teachers have sprung up to fill this void left by the institutions who are actually tasked with supporting teachers. Rather than leave these ecosystems to chance, schools should invest in them internally so teachers see an institutional recognition of their needs and growth.

Will this solve everything facing the coming crisis in the teacher workforce? Probably not. But is it better than what most schools are doing today? Absolutely.