In a recent blog post Justin Baeder from the Principal’s Center explored the Amazon.com Annual Letter to Shareholders. Justin did the hard work of reading the full letter (which can be a little tedious unless you really like corporate filings), and he found one key takeaway that school leaders can apply to motivate their teams. He sums it up with a story Bezos tells in the Amazon letter about a friend who recently tried to learn how to do handstands.

A close friend recently decided to learn to do a perfect free-standing handstand. No leaning against a wall. Not for just a few seconds. Instagram good.

She decided to start her journey by taking a handstand workshop at her yoga studio. She then practiced for a while but wasn’t getting the results she wanted. So, she hired a handstand coach. Yes, I know what you’re thinking, but evidently this is an actual thing that exists.

In the very first lesson, the coach gave her some wonderful advice. “Most people,” he said, “think that if they work hard, they should be able to master a handstand in about two weeks. The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you’re just going to end up quitting.”

Unrealistic beliefs on scope – often hidden and undiscussed – kill high standards.

To achieve high standards yourself or as part of a team, you need to form and proactively communicate realistic beliefs about how hard something is going to be – something this coach understood well.

Justin Baeder, in his take on Bezo’s letter, likens the handstand story to the changes that schools try to enact every day. Baeder talks about the impact of well-intentioned schools and districts who use high standards, accountability, and measurement to motivate teams towards meaningful change. He also points out the painful truth that most of those intentions are never realized. As a result, most schools still look and feel the way they did a century ago. But there’s a good reason for that.

Changing a school is about the hardest thing anyone can do.

Schools are unbelievably complex places. While most leaders of organizations have to manage multiple stakeholders, school leaders have to address the needs of teachers, parents, other staff members, community expectations, news reporters, and…oh yeah…students. Often, the expectations of these diverse constituent groups are in direct conflict with one another. As a result, no matter what decision you make as a school leader you’re bound to disappoint someone. Also, each person that walks into a school leader’s office has had one common experience: they have all been a student in a classroom. This experience leads many people to the–often misguided–conclusion that they are an expert on schooling.

As a result, school leaders take in a great deal of conflicting information from a passionate crowd of people. In an effort to accommodate everyone, the list of initiatives gets very long very quickly. And again, the expectations can often directly oppose one another.

Consider the following example.

Principal Jones wants to establish a school culture where students take learning seriously and maximize their opportunities to learn. After surveying teachers, students, and parents, he identifies two problems:

Problem 1: Students are coming to school dressed inappropriately, conveying a disrespect for the learning environment.

Solution: Establish a strict dress-code, send students to the office when they are out of compliance

Problem 2: Students are not getting enough time in class to practice critical skills. Classes begin rather informally and students often have nothing to do while the teacher takes attendance.

Solution: Teachers must initiate instruction as soon as the bell rings and should not take time to perform administrative tasks.

Systems are put in place to monitor compliance with both initiatives. Both teachers and students are held to high expectations. Administrators doggedly document time on task in the first 5 minutes of each period along with the number of dress-code violations.

Teacher A chooses to prioritize time on task over dress-code-compliance. He establishes routines to get students into his classroom quickly during the passing period and begins silent reading immediately. As soon as the bell rings, Teacher A begins class with an engaging warm-up activity connected to the silent reading passage.

Teacher B chooses to prioritize dress-code-compliance over time on task. She has students line up at the door during each passing period for a careful inspection of their appearance. She allows each student who is in compliance into her class. Students who are out of dress code are given a discipline referral and sent to the office. Teacher B habitually starts class 1 to 2 minutes late to allow time for student inspection. During that time, students are told to begin working on an assignment written on the board. Students typically begin work on the assignment, but do not have a mechanism to ask for help if they are confused since their teacher is in the hallway monitoring dress code.

Principal Jones performs a walk-through of Teacher A’s class during 2nd period. Upon completion of walk-through, he documents that 8 students were out of dress-code. During 3rd period, he performs a walk-through of Teacher B’s class. He documents that 3 students were off-task for the first 7 minutes of class. He also documents that 9 students walk into class 12 minutes late after returning from the office, where they were sent for being out of dress-code. Late students are not given the opportunity to catch up on the work performed during the first 12 minutes of class and take an additional 3 minutes to get their materials, figure out what everyone else is doing, and join the class.

After six months, dress-code violations do not go down and instructional time does not go up.

Both initiatives are considered a failure.

The scenario described above is a little benign, but not uncommon. While both problems might be a hindrance to the type of culture Mr. Jones wants to establish, their solutions are in direct conflict with one another. One solution requires students to be out of class, the other requires them to be in class. One requires teachers to focus on administrative tasks, the other on instructional tasks.

School leaders should be prepared for the complex nature of trying to initiate change in the school climate. However, without specifically communicating this complexity, people are left to make their own decisions, which can create chaos. Additionally, expectations can send conflicting messages. As a result, no one really knows what to do.

Change has to happen tomorrow!

Time is a scarce resource in schools. After all, each kid only gets one chance at 2nd grade. As a result, when a school wants to make a big change, school leaders are expected to accomplish that change in one year (if they’re lucky). Additionally, since the bulk of a school’s employee’s time is spent directly in charge of students, faculty and staff are expected to acquire the requisite knowledge, skills, and mindset they need to implement a new initiative in a few days, or even a few hours. This hurried approach to change results in a “bullet-list” approach to expectations. While the list of expectations might seem simple enough on a piece of chart paper, their relationship to the rest of the school context is often ignored, and the depth of each bullet is rarely explored.

Complex Change + Short timelines = disappointing results

Complexity and urgency are a dangerous combination. The latter can cause an organization to ignore the former. Additionally, schools do not often take advantage of the “research and development” mindset that other organizations do. The luxury of testing something, refining it, taking time to work out the kinks, and then rolling it out over a couple of years almost never happens in a school.

However, neither the urgency nor the complexity are going away. And school leaders still need to accomplish change. So what are you going to do about it?

There’s one surefire answer: don’t lower your standards!

It’s time to get real

Consider the handstand referenced by Bezos again. While on its face, a handstand seems easy enough to do–like changing a literacy strategy or implementing technology tools in the classroom–you may not be perfect at the start, but if you just put your hands on the ground and kick your feet in the air for a couple of weeks, you should be able to get it, right?

Wrong.

A handstand is a complex set of actions. Each action requires attention, training, and (most importantly) practice. In reality, kicking your feet in the air probably doesn’t even need to happen until week 2 of your practice. But what on earth do you have to do before that first kick? And what do you do after the first kick?

You need a coach.

Good coaches motivate. Great coaches guide. You need someone who knows where to go, how to get there, and what equipment you’ll need along the way.

When a school wants to change something, everyone needs a coach. Don’t be frightened by this. The good news is that the same complexity that creates some of the problems school leaders face can be the solution here. Each person in your universe can be a coach, not just the people with the word “coach” in their title. By building supportive teams, and establishing structures for them to interact with one another, everyone gets a chance to be coached on their own path toward success. This collaboration also helps build a playbook where everyone understands the map for each play. If you allow everyone’s perspective to inform the playbook, the result is clearer expectations, greater buy-in, and better aligned teams.

But clearer expectations aren’t enough. You also need to be realistic.

It’s time for a little math

Remember the equation from earlier:

Complex Change + Short timelines = disappointing results

Nothing a coach can do will change this maxim. It is unbreakable. So you need to account for it. That’s where the handstand coach created real value for Jeff Bezo’s friend. Before communicating the playbook, before the practice began, the coach said this:

“Most people,” he said, “think that if they work hard, they should be able to master a handstand in about two weeks. The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you’re just going to end up quitting.”

It’s crucial to take a long hard look at the journey before taking a single step. Consider the equation above with a slight variation:

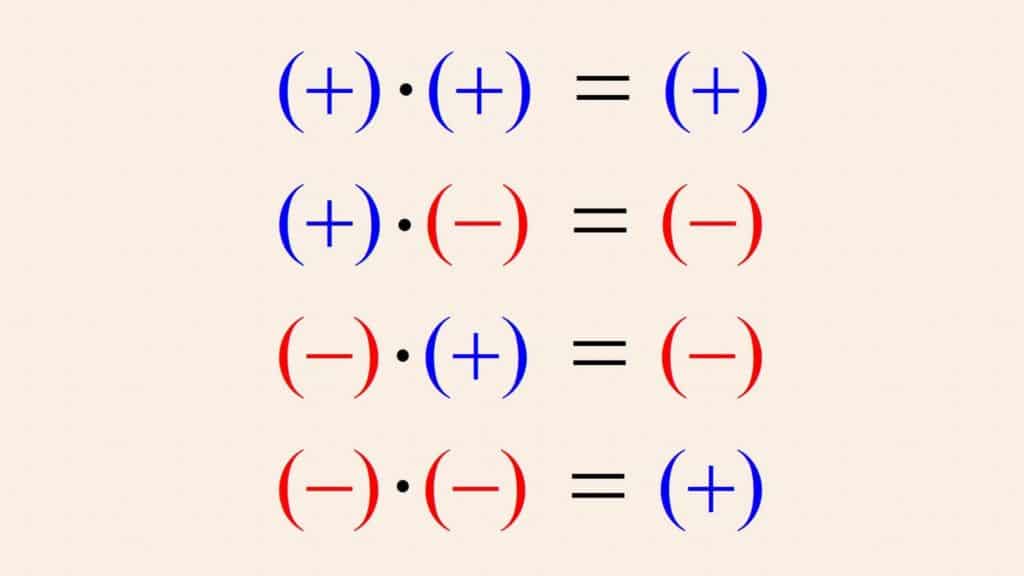

(y)Change * (x)timelines = (n)results

Equations are composed of variables. Some are dependent and some are independent. In this equation, there is relationship between y and x. Your goal is to get a positive n (get it? positive results!).

In case you need a little refresher on multiplying integers, here’s the chart you need:

Now you have all the information you need to find a positive outcome for n. If the change you seek is more complex, you need a longer timeline. If you don’t have much time, you need to reduce the complexity. It’s that simple. And if you’re not sure how complex something is, ask your coaches. That’s their job.

Now you have all the information you need to find a positive outcome for n. If the change you seek is more complex, you need a longer timeline. If you don’t have much time, you need to reduce the complexity. It’s that simple. And if you’re not sure how complex something is, ask your coaches. That’s their job.

Realistic expectations and great coaches…they’re the secrets to great handstands and great schools.